Revolutionary Jujitsu in the 2020s

The last year has offered a preview of the horrors that capitalism is preparing for us. A pandemic has killed millions and trapped billions inside. Major cities like Sydney and San Francisco were covered in smoke as a result of unprecedented wildfires. As I write these lines, my family in South Texas, where I grew up, has been without power for four days due to a snowstorm. Economic growth has crashed at rates never before seen outside of wartime. And with the capitalist crisis, the geopolitical tensions between the Great Powers are growing as well.

The naive optimism of the 1990s and early 2000s has turned into panic and dread: more and more people understand that we need to act now to prevent a catastrophe.

Yet while the situation demands audacity and courage, many of us feel helpless and completely alone. I often feel that way, and young people around the world are struggling with despair. To save our civilization, and even our species, we need to end capitalism as soon as possible — but can we even get out of bed?

The material conditions exist to provide every single human being on the planet with a comfortable and dignified life. We have all the technology we need to prevent the worst of climate change. Social relations, however, remain completely outside of rational control. Technological advances are not making life easier — they are used to increase surveillance, mass manipulation, and repression.

In this depressing landscape, there are also explosions of hope. Last summer saw the largest protests in the history of the United States. Before that, the Yellow Vests erupted in France. From one moment to the next, the unstoppable power of the workers and the oppressed can become visible. In moments like these, we see the potential to control the destructive anarchy of the so-called „free market,“ and create a society for the benefit of all.

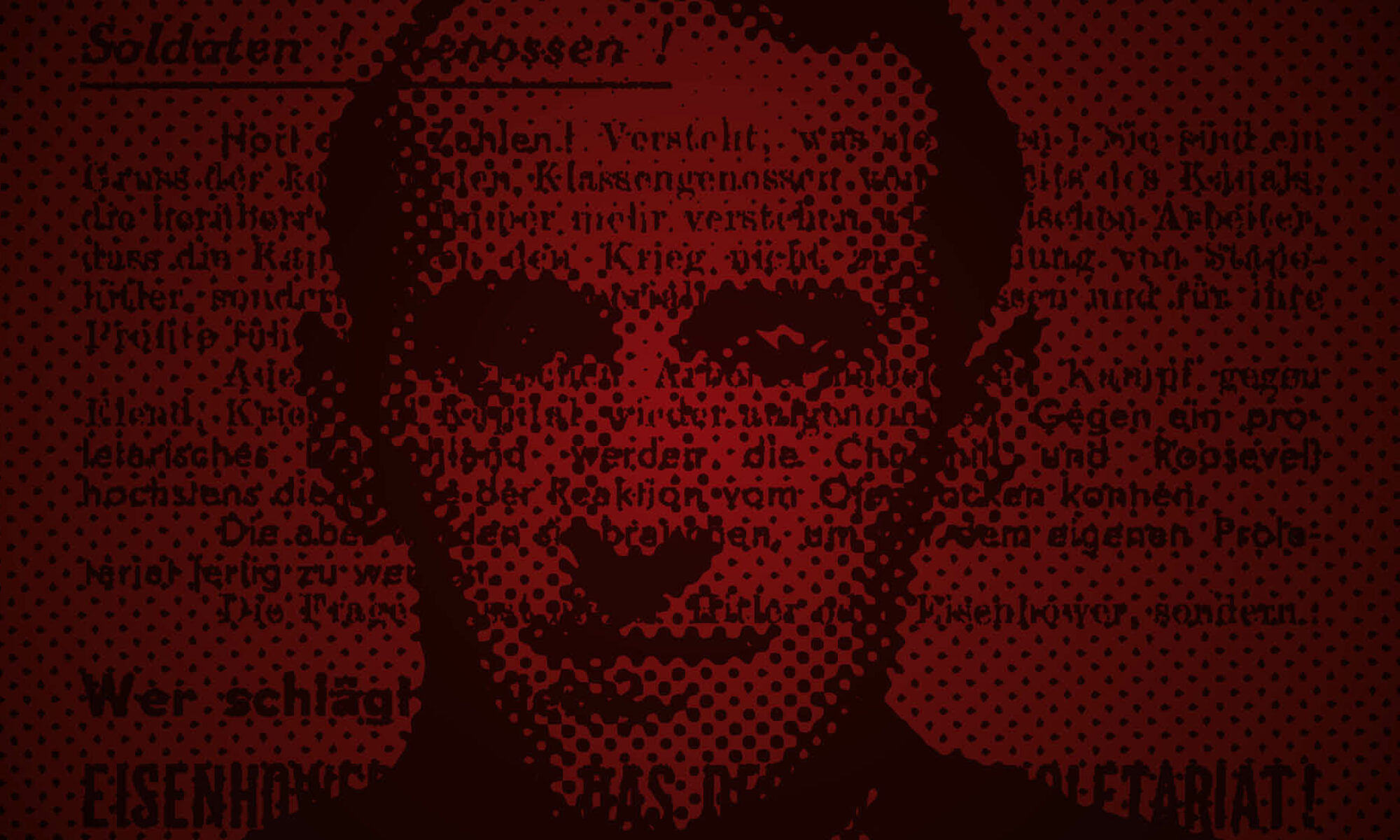

Resistance fighters against German fascism, such as Martin Monath, can be a source of inspiration in daunting times. They were facing a terrifying apparatus for mass murder. But they understood that no situation is truly hopeless. Monath and his comrades set out to destroy the Nazi armies from within. They turned to the German “workers in uniform,” calling on them to rebel against their officers and the Hitler regime. They called for working-class action to put an end Nazi barbarism. Their aim was to transform the imperialist war in an international civil war against capitalism and Russian bureaucracy installed atop the ruins of the October Revolution. Put simply, they wanted to act upon history, to change history.

This book focuses on just one life. But Monath was no lone fighter — he was one of thousands of revolutionaries who took up this campaign. They were not starting from scratch: they could base themselves on the traditions of earlier socialists who had fought against imperialist and colonial wars. These previous struggles, even when they ended in defeat, left behind a program and a strategy whose current significance, even after so much time has passed, is undeniable.

Monath, the editor of a paper called „worker and soldier,“ was neither a worker nor a soldier. He was, more than anything, a dreamer — but one who worked diligently to make his dreams a reality. This non-worker, non-soldier gave a voice to workers and soldiers — a voice that would help them become more than just a mass of maneuver for the plans of the capitalists, their generals, and their politicians.

Jujitsu

Jujitsu is a martial art that was developed in feudal Japan. How could an unarmed peasant defend himself against a samurai with heavy weapons and armor? By turning the samurai’s weight, aggression, and arrogance into a weapon against him. Use the enemy’s own force against him — this is the principle of jujitsu, which can be translated as the „art of yielding.“

When working-class suffragettes from East London organized themselves under the leadership of soon-to-be communist Sylvia Pankhurst in the years before World War I, they trained in jujitsu to protect their demonstrations from police attacks. What works against a samurai, after all, can work against a bobby. The press dubbed this „suffrajitsu.“

Why do I mention this (besides the fact that it is cool)? Because this is a good metaphor to think about revolutionaries‘ work in times of war.

When the capitalists build up their monstrous killing machines, forcing millions of young men (and now people of other genders) to put on uniforms, they never appear more powerful. Yet the armies they create can become forces for social revolutions that sweep away bourgeois rule. The trick is to turn the capitalists‘ massive force against them.

The Trotskyists in World War II might appear to have been wildly overconfident, aiming to take down the greatest military might that Europe had ever seen. Yet like jiujitsu fighters, they aimed to turn the Nazis‘ strength against them. It had been, after all, the soldiers of the Kaiser and the Tsar who had chased off those two cousin-monarchs.

The bourgeoisie creates its own gravediggers, and the capitalists‘ war can be turned into a civil war against the capitalists. For this, the workers in uniform need a consciousness based on the lessons of earlier struggles. The Trotskyists were fighting to maintain the historical memory of their class.

War is when capitalist society sharpens all of its contradictions to a white hot glow. And yes, wars sometimes lead to new forms of capitalist domination. But just as often, they end with social explosions.

Today, the growing contradictions of capitalism might not lead to a new world war in the short term. But there will be new military confrontations. And young revolutionaries need to prepare for this now, by studying the work of the Trotskyists in France, as well as many other antimilitarist experiences.

Reformists will say this is „utopian“ and we should be content with the misery of the possible. What is truly utopian is to hope that the coming catastrophe can be averted with minor reforms to capitalism. The only realistic option is to prepare for a revolution that will topple the capitalist class that is leading humanity to an abyss.

New Research

I am very pleased that this book is being published in Argentina and France — two countries where Trotskyist ideas have a certain influence among the vanguard of the workers and the oppressed. France is where Monath, a Jewish German Trotskyist, carried out his struggle.

This book was first published in Germany in 2018. The following year, I found a new trove of documents at the Berlin Reparations Office, whose archives are located in the former headquarters of an insurance company. The building from 1936 still retains the monolithic architectural style of Nazi times. Karl Monath spent more than ten years fighting for reparations for his murdered brother. He had to provide piles of documentation, and with that I was able to fill some holes in my earlier research. The English edition of the book, published in the UK in 2019, included new details such as Martin’s middle name, his school, or a map of the neighborhood where he grew up. Additional photographs were provided by Naomi Baitner, who is the daughter of Martin’s sister Lotte.

Besides the many people I thanked in the introduction to the German and English editions, I would like to express my deepest thanks to the comrades who did the translations to French and Spanish. I am sorry I am not a better writer! Also, thanks to the editors from Éditions Syllepse in Paris and Ediciones IPS in Buenos Aires, who have taken on the task of making revolutionary ideas available to new generations joining the struggle against capitalism. Finally, I would like to thank everyone who in the coming years will help get the story of Martin Monath turned into a movie.

Nathaniel Flakin

February 25, 2021, Berlin

(Just around the corner from Martin’s last address in Berlin, Gutenbergstraße 4 in Charlottenburg)